That’s two in one day: Anthony Minghella this morning and Sir Arthur C Clarke this evening. Two great people whose respective talents have entertained and inspired different but overlapping generations, with Anthony Minghella leaving us, far far too soon and Sir Arthur after a good innings and a long life. The quality of the rest of our lives has just dropped a tad.

That’s two in one day: Anthony Minghella this morning and Sir Arthur C Clarke this evening. Two great people whose respective talents have entertained and inspired different but overlapping generations, with Anthony Minghella leaving us, far far too soon and Sir Arthur after a good innings and a long life. The quality of the rest of our lives has just dropped a tad.

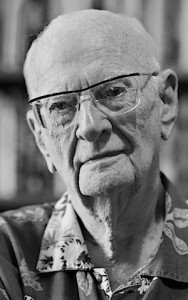

While Anthony Minghella I knew only through his work, I have been lucky enough to have the privilege of meeting and corresponding with Arthur Clarke. I don’t by and large do heroes, but, if I were backed against an obelisk and forced to choose, he’d be one of mine as someone who, along with my father, was probably more responsible than anyone else for my passion for and career in science and technology. I was roughly nine when I read Glide Path, his fictionalised account of his work on early ground approach radar and was mesmerised less by the human plot than by the description of the process of trial, error, lateral thinking and sheer slog that goes into the development of a new technology, from mere idea – however ambitious – to working system. I’ve often had to hold to that early memory.

When I was ten, I was taken by my father to see 2001 where, apart from the obligatory twenty-minute period of uncomprehending boredom during the infamous psychedelic transit sequence, I was utterly entranced by the scope of the unfolding vision and grand themes. I entered that Edinburgh cinema determined to be a fighter pilot and left it set on becoming – no, not an astronaut – but a designer of robots. Megalomania sets in early.

My teenage years were spent consuming every scrap of Sci-fi – good, bad and downright awful – that I could spend my meagre income on, with anything of Arthur C Clarke’s being right at the top of the list. Having worked my way through the Clarke canon, I realised that, for me, his work fell into two great categories: the Big Ideas and the Big Passions. The former were the great epic space-centred novels, breathtaking in the imagination and somewhat detached in the characterisation. The latter were his books that described two parts of our own world – the world beneath the waves (The Deep Range) and the island of Sri Lanka, thinly disguised by its Sanskrit name of Taprobane in The Fountains of Paradise. It was in those books that his prose came alive and carried to his readers’ hearts the beauty of what he saw and his awe of and love for his subjects.

It took a couple of decades, but I finally did become a designer of robots, albeit not in any form that remotely could have been predicted, when working on the robot characters for our game, Starship Titanic. It was also at that time that I was both fortunate to meet him through the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund, of which he was a patron and to make my first visit to that most beautiful and troubled island of Sri Lanka. On arriving at our hotel in the heart of the country, I’d not even had a chance to rinse the red dust of travel from my face when the hotel manager handed me a fax: “Heard you were in the country. Would be delighted if you could visit in Colombo. Arthur Clarke.“. An invitation not to refuse. We arrived at his compound in Colombo for afternoon tea, and spent the afternoon and much of the evening on an eclectic conversational tour of the galaxy, starting with the poor quality of his Internet connection (ironically, delivered via a geostationary satellite whose very notion he’d invented), ranging through his views on the Drake equation and ending up on our shared concern for the future of life on our planet, via multiple digressions and anecdotes. All this whilst attempting a guarded friendliness with his affable but mildly incontinent pug – showing willing whilst avoiding damp shoes. Since then, we’d had a intermittent e-mail correspondence, mainly around the work of his charitable Clarke Foundation – he always answered, was never worse than mildly and politely acerbic in the face of daft questions and was never less than pin-sharp and entertaining in equal measure.

In the remembering of the man and his work, I can’t do any better than use exactly the same Rudyard Kipling quote that he used at the end of an article published only last month in Sri Lanka’s Sunday Leader:

“If I have given you delight by aught that I have done, let me lie quiet in that night which shall be yours anon; And for the little, little span the dead are borne in mind, seek not to question other than, the books I leave behind.“.

It’s perhaps fitting that, as I write this late at night in the depths of the Scottish Highlands, to me he has still died tomorrow.